ODPi Offers Olive Branch to Apache Software Foundation

The rift between the Open Data Platform Initiative (ODPi) and the Apache Software Foundation (ASF) is on the mend, thanks in part to a peace offering by ODPi, an admission of being indelicate, and a $40,000 check. It may not pacify everybody in the Apache Hadoop community who feel threatened by ODPi’s presence, but at least it’s a start.

With its financial commitment, ODPi becomes a gold sponsor in the ASF, which manages 350 open source projects, about 10 percent of which could be considered “big data” projects. ASF Vice Chairman Greg Stein, one of the original founders of the open source organization, welcomed ODPi into the fold. “We are pleased to welcome ODPi to the ASF Sponsorship program and their support of Apache big data projects,” Stein said in a press release.

Stein’s quote may not sound like much, but it appears to be a major step forward for ASF in recognizing ODPi as a legitimate player in the ongoing development of open source big data projects, specifically those around Hadoop. ODPi Director of Program Management John Mertic hopes the move will diffuse the tension–real or imagined–between ODPi and ASF.

“There’s a degree of FUD [fear, uncertainty, and doubt] and there’s a degree of, we probably didn’t do our best due diligence of addressing the problem on the front-end,” Mertic tells Datanami in an interview at this week’s Apache: Big Data North America conference held in Vancouver, British Columbia. “That’s sort of been the reality since it was launched.”

Mertic started working with the ODPi in late 2015, when the Linux Foundation took over management of the project that started as the Open Data Platform (ODP). The ODP was founded in February 2015 by Hortonworks (NASDAQ: HDP), Pivotal, IBM (NYSE: IBM) and others to create a standard specification for Hadoop that customers and vendors could write to, instead of doing the work to test against multiple distributions. The organization delivered the first reference specifications in March.

The project was met with controversy, from ASF members, as well as from Hadoop distributors Cloudera and MapR Technologies, who questioned the need for its existence. “The announced Open Data Platform benefits Hortonworks marketing and provides a graceful market exit for Greenplum Pivotal,” wrote MapR CEO John Schroeder. “As a vendor-driven consortium, membership is only for enterprises with serious money–it ought to be called the ‘Only Dollars Play’ alliance,” said Cloudera co-founder and chief strategy officer Mike Olson.

The Linux Foundation didn’t create the ODPi, but the non-profit organization–which has been contracting with the ASF for the last few years to produce and run the Apache Big Data and ApacheCon series of conferences–appears to be willing to work to make it succeed. For Mertic, that means being conciliatory of the ASF’s position, saying mea cuplas, and understanding the concern expressed by many ASF members.

“We just didn’t do our best job in engaging and figuring out what the true issues were,” Mertic says, “and at least having the dialog in place [to figure out] what are the problems, how do we address them, and let’s figure out how to move past them, because we really both have our eyes on the same prize here: How do get more people using Hadoop.”

Shared Proprietary Enemy

With so many projects, the ASF is constantly looking for sources of funding to power test servers, buy bandwidth, and do the other things that software development organizations need to do. To that end, the $40,000 will help. But for ODPi and the Linux Foundation, the money and Gold status (it could have spent $100,000 for Platinum status) are secondary to building a bridge with the ASF.

“We’re committed to making sure of Apache’s success,” Mertic says. “Our success depends on the upstream project success. Furthermore we’re not looking to do development separate from Apache. We want Apache to own the development process. We want them to own the projects process….We want Apache to keep doing what Apache’s great at, which is building amazing, incubated, governed projects.”

“We’re committed to making sure of Apache’s success,” Mertic says. “Our success depends on the upstream project success. Furthermore we’re not looking to do development separate from Apache. We want Apache to own the development process. We want them to own the projects process….We want Apache to keep doing what Apache’s great at, which is building amazing, incubated, governed projects.”

Both the ASF and ODPi want to promote Apache Hadoop and the family of projects that live under Hadoop. But in Mertic’s view, the ASF is ill-equipped to deal with the macro problem of making sure that the projects work together as a united whole.

“The ASF by its nature is a very decentralized organization. You have a vice president for each individual project,” he says. “Apache is not into umbrella projects. They’re more about getting individual projects to be successful and driving the infrastructure to do that. We have the ability to help provide clarity around the umbrella level.”

Some members of the larger Hadoop community have accused the ODPi of fostering a situation that encourages forking of Hadoop into multiple, splintered projects. Those concerns are misguided, Mertic says. “We’re not doing that,” he says. “We have no interest in owning our own IP, we have no interest in having our own separate Hadoop or maintaining it. We are dead focused on letting Apache focus on development, and we can help provide use cases or insight…Let’s stop this conversation about forking or competition. We’re putting our ducks in your basket.”

What’s more, the current lack of cohesion among Apache big data projects and the current state of ad-hoc integration are creating risk for the Hadoop ecosystem, he says. “We’re at a ripe time here [with the potential of big data] and frankly its’s a failure on us from an open source perspective if we can’t get our stuff together enough before somebody proprietary comes in and solves the problem,” he says.

An Apache’s View

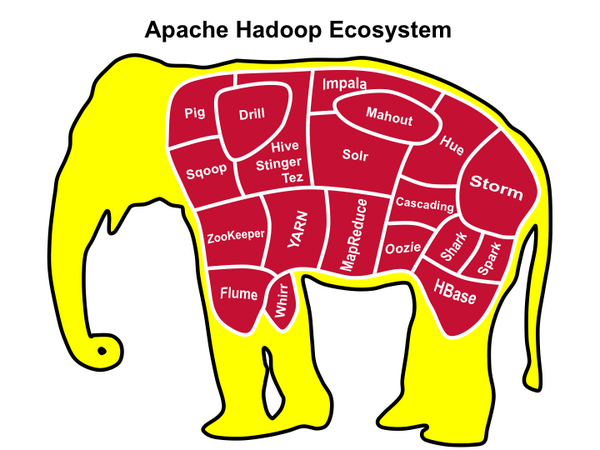

The Hadoop ecosystem keeps growing and growing.

Higher-ups in the ASF weren’t available for comment. But the ODPi does have the nod of approval of Roman Shaposhnik, who was previously the vice president of the Apache Incubator (which is itself an Apache project) and is currently director of open source at Pivotal, which is a founding member of the ODPi.

In Shaposhnik’s view, concerns about forking and vendor influence over the ODPi are overblown. In fact, if anything, the ODPi helps protect Hadoop customers against the threat of vendor lock-in.

“If the software that you’re dealing with is undergoing a high rate of development, then you end up in fractured vendor space, where vendors essentially are picking features they like,” Shaposhnik tells Datanami. “Even though everything is open source, the feature that vendor A is selling isn’t compatible with the feature that vendor B is selling. So if you’re developing an application on such a platform, you cannot move freely between vendor A and B. ODPi is trying to solve this problem by getting all the vendors to agree on what are the feature sets and use cases that we’re trying to address.”

Hadoop co-creator Doug Cutting welcomes the investment that ODPi made in the ASF, saying the extra money will be well spent. However, when it comes to supporting the ODPi, the Cloudera chief architect withheld his backing.

“I don’t think it’s necessary,” he said today at the Apache Big Data conference this morning, where he delivered a keynote. “It could be dangerous.”

Asked whether Cloudera will rethink its decision not to join the ODPi, Cutting said that it’s unlikely to occur, although he added that this position could change. As it currently sits, the vendors supporting 75 percent of commercial Hadoop deployments are not members of ODPi, he said.

Who Picks the Winners?

One could make the argument that Apache itself is best suited to decide which features are the most important ones to be included in the project. After all, that’s what developers do–figure out what people need, and then make software that does that.

But in the case of Hadoop, Shaposhnik says, there’s one key factor that makes this all but impossible. It all started 20 years ago, when the Apache Software Foundation had but a single project–the HTTP Server–which eventually became the standard for Web servers used across the world.

“The great thing about the HTTP server was it was a self-contained piece of technology. Nothing else needs to be attached to it,” Shaposhnik says. “All the integration happens with the vendors. Hadoop was one of the first examples where that wasn’t true at all. Basically it’s a collection of projects. Then the question is, who’s in the business of making sure these projects can basically provide a meaningful platform instead of being just independent projects. Historically, ASF hasn’t tackled that.”

In fact, the idea that the ASF should be setting specs–that is, picking what features are important and what features are not important–is anathema to the ASF’s neutrality regarding technology. “The moment the ASF gets opinionated about what happens between two different projects, that’s the moment when we violate the principle that we are picking the runners and not the winners,” Shaposhnik says. “That’s not the way ASF operates. ASF as a whole doesn’t have the authority to tell projects what to do.”

It’s a delicate balance, to be sure–one that’s exacerbated on the one hand by the high stakes of the enterprise software business, and on the other by the tradition of a distributed chain of command in the open source community. The apparent chaos that exists in the ASF–how many more real-time streaming data analytic projects do we really need?–is actually the secret of its success. Take that freedom away, or demand regimented processes instead, and who knows what might happen.

In Shaposhnik’s view, the ASF, by its very nature, is not equipped to regulate itself to such a degree that the Hadoop family of products can be hammered into a cohesive, workable whole, and not just a mish-mash of do-it-yourself parts. The various ASF projects that compose what we know as the modern Hadoop ecosystem aren’t currently equipped to make sure that the respective projects don’t break with every new release, he says. “There’s not a single center of gravity,” he says.

So why not let ODPi work downstream of the developers at the ASF, who are doing a fabulous job innovating at an increasingly amazing pace? It may take some time to diffuse the perceived negatives about the ODPi–that it’s encouraging forking of Hadoop, that it only benefits vendors, that it’s pay to play, and that it will slow innovation. But if Apache insiders like Shaposhnik are convinced that something like ODPi is necessary for Hadoop to succeed in the long run, then perhaps the controversy surrounding ODPi was overblown.

“We don’t dabble,” he says. “We’re trying to standardize what enterprise have done last couple of years and have had some success doing. We’re in the business of putting those kinds of design principles on paper and making sure that all the members of ODPi respect it”.

Related Items:

ODPi Defines Hadoop Runtime Spec; Operations Up Next

Making Sense of the ODP—Where Does Hadoop Go From Here?

Hadoop’s Next Big Battle: Apache Versus ODP